Part 1: The Recruiter Manual

Tools & Curriculum

ID&R Manual

Foreword & Preface

Foreword

The Office of Migrant Education (OME) is pleased to provide this update to the Migrant Education Program Identification and Recruitment Manual—an essential resource for migrant educators nationwide.

This publication is an integral part of OME’s Identification and Recruitment (ID&R) Initiative, which was established in 2000 to help states conduct timely and accurate identification and recruitment of eligible migratory children. This manual was revised to reflect changes to the program enacted in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

Finding and enrolling eligible migratory children quickly and efficiently is the foundation of a strong Migrant Education Program (MEP). Migratory families often experience difficulty in receiving continuous, high-quality educational services because of their high rate of mobility, cultural and language barriers, social isolation, health-related problems, disruption of their children’s education, and the lack of resources in the areas in which they live and work. Before migratory children can be served, however, they must be found and enrolled into the MEP without delay.

This publication provides technical assistance on how to recruit effectively and how to set up an efficient and accurate ID&R system. It is my hope that this comprehensive resource will help renew the commitment of all MEP recruitment staff to the timely and proper ID&R of eligible migratory children.

I appreciate the dedication and service of all who work each day on behalf of migratory children and their families. It is more crucial than ever that we use every available resource and innovative strategies to identify and serve the children of our hard-working migratory farm workers and fishers. I look forward to continuing our work together to strengthen this gateway to the provision of vital MEP services.

Lisa Gillette

Acting Director

Office of Migrant Education

U.S. Department of Education

Washington, D.C.

Disclaimer:

This manual was produced with the assistance of the U.S. Department of Education Contract No. ED-08-CO-0111 with Center for Migrant Education at Texas State University-San Marcos. Irene Harwarth served as the contracting officer’s representative. It was updated with the assistance of the U. S. Department of Education Contract No. ED-ESE-15-C-0035 with the Research Triangle Institute. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service or enterprise mentioned in this publication is intended or should be inferred. This manual contains examples of, adaptations of, and links to resources created and maintained by other public and private organizations. This information is provided for the reader’s convenience and is included here to offer examples of the many resources that readers may find helpful and use at their discretion. The U.S. Department of Education does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of this outside information. Further, the inclusion of items and examples do not reflect the importance, nor are they intended to represent or be an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any views expressed, or products or services.

Purpose

The Migrant Education Program (MEP) National ID&R Manual is designed to assist state educational agencies (SEAs) in developing state identification and recruitment (ID&R) systems for the MEP, thereby correctly implementing the MEP statute and regulations. The SEA is responsible for the proper and timely ID&R of all eligible migratory children in the state, including documenting the reason why each child has been determined to be eligible for the MEP. Part I of this manual provides general information and advice regarding the recruiter’s role in the ID&R process and in ensuring the correctness of eligibility determinations. Part II of this manual provides general information and advice regarding the state and/or regional administrator’s role.

This manual is not intended to be prescriptive. The examples provided in this document should not be viewed as the "only" or the "best" way to identify migratory children. Instead, they are provided as tools to help practitioners consider the range of options available and to stimulate thinking about this topic. This document is one of many resources for SEAs and local operating agencies (LOAs) to use as they determine how best to identify and recruit eligible migratory children in a manner consistent with the requirements of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). While users of this manual may wish to utilize or adapt the information presented here, they are free to develop their own approaches that are consistent with applicable federal statutes and regulations.

This manual is meant to be read in conjunction with the following companion documents:

- the authorizing statute

- the applicable regulations

- the 2017 Non-Regulatory Guidance for Title 1, Part C, Education of Migratory Children (NRG)

- the U.S. Department of Education’s (ED) guidance on other federal programs that are relevant to the MEP (such as Title I, Part A, and Title III)

- state requirements, policies, and guidance

The statute and regulations are binding on both ED and its grantees and cannot be changed outside of the reauthorization and regulatory processes. By comparison, policy guidance is not binding on grantees. Therefore, SEAs may adopt policies and procedures other than those found in the MEP’s NRG or this technical assistance manual, provided that they reflect reasonable interpretations of the MEP statute and ED regulations. Words in the NRG and this manual like “must” and “shall” are used to indicate statutory and regulatory requirements.

States are responsible for making decisions regarding the best way to operate the MEP consistent with federal and state regulations. It is critical that staff at the SEA and local level realize that they should not continue practices simply because they are based on longstanding policy, but rather should adjust to current needs, research and experience with what works.

The National ID&R Manual is meant to provide general advice on ID&R.

Audience. The primary audience for this manual is SEA administrators. However, it should also be of interest to ID&R coordinators, ID&R contractors, regional administrators (the individuals who administer ID&R within each state), local administrators, recruiters, home-school liaisons, and advocates for migratory children and youth. Part I of this manual explains the major duties and responsibilities of the recruiter. Part II discusses the administration of an ID&R system. Recruiters and administrators should read their own section of the manual as well as their counterpart’s in order to understand the full scope of responsibilities. Although Part I and Part II can be read separately, reading both parts together helps to provide a more complete understanding of a MEP ID&R system.

Organization. This manual is organized as follows: Chapter, Section, Subsection, and Paragraph Header. Below is an example of how information is visually organized:

Chapter 1.SectionSubsection. The recruiter is responsible for interviewing children, families, and youth to determine if they are eligible for the Migrant Education Program. Paragraph Header. The recruiter is responsible for interviewing children, families, and youth to determine if they are eligible for the Migrant Education Program. |

Style. This manual follows the conventions of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association.

Background

Every Student Succeeds Act. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) reauthorized the ESEA. A key purpose of the ESEA, as amended by the ESSA, is to provide all children with the opportunity to obtain a high-quality education that will enable them to meet the same challenging academic standards in their state that all children are expected to meet.

The Migrant Education Program. The MEP is authorized by Title I, Part C of the ESEA, as amended. Under the MEP, ED provides formula grants to SEAs to establish or improve education programs for migratory children. The general purpose of the MEP is to ensure that migratory children fully benefit from the same free public education provided to non-migratory children. To achieve this purpose, the MEP provides financial support to SEAs and LOAs to address the unique educational needs of migratory children, including preschool migratory children and migratory children who have dropped out of school. In order to meet the goal of supporting the academic success of eligible migratory children, the MEP must first identify and recruit these children.

Primary Goal of the MEP. The primary goal of the MEP is to help ensure that all eligible migratory children meet challenging academic standards AND graduate with a high school diploma or complete a High School Equivalency Diploma (HSED) that prepares them for responsible citizenship, further learning, and productive employment.

ID&R Initiatives and Research. Since the MEP began in 1966, many states and educational organizations have produced publications that describe the ID&R process and provide useful suggestions and tools. Some of the most well-known national efforts include:

- 1981. The Migrant Education Recruitment and Identification Taskforce Project (MERIT) developed tools for ID&R, such as a national identification document and other training materials. ED provided funding for this effort through a grant awarded to the Indiana Department of Education under former section 143 of the ESEA.

- 1986. The Louisiana Department of Education published the Systemic Methodology for Accountability in Recruiter Training Manual (the SMART Manual). ED provided funding for this effort through a grant under former section 143 of the ESEA.

- 1989. The Pennsylvania MEP produced four ID&R publications: (1) a guide for recruiters, (2) a guide for administrators, (3) a reference supplement, and (4) a research report entitled The Effects of Migration on Children: An Ethnographic Study. ED provided funding for this effort through a grant under the former section 143 of the ESEA.

How to Use the Manual

Language. Although ease of reading and clarity were important in the development of this manual, the text may present some difficulties, particularly for those who speak English as their second language (ESL). Because this is a technical manual, the language has not been modified; however, language accessibility has been taken into consideration in developing the National ID&R Curriculum, which supplements this manual.

Chapter Learning Objectives. Learning objectives are included at the beginning of each chapter. The lists of objectives will offer the reader a preview of the material covered in each chapter as well as a tool to enable the reader to self-check to see if he or she has understood the major concepts in the chapter. Checklists that mirror the learning objectives in each chapter and depict concrete action steps that recruiters and administrators should take after mastering the material in the National ID&R Manual are provided in Appendix XVI.

Lessons Learned. In recognition of the experience of the ID&R community, OME has interspersed “lessons learned” from veteran ID&R staff throughout the manual. Lessons learned reflect advice regarding both strategies to adopt and pitfalls to avoid. These lessons learned help new and veteran recruiters benefit from the experience of others.

Tips from MEP Staff. Throughout the manual, the reader will see quotations that are indented and italicized. These quotations are often tips, pieces of advice, or “good ideas” from MEP practitioners. Some are taken from state and past federal manuals, which are referenced. Others represent powerful ideas heard from recruiters and administrators at meetings and forums. In some cases, the wording has been changed to make the idea clearer.

Resources and References. Appendix XVII: Resource and Reference List includes citation information for and links to resources referenced in the manual, including general resources, useful websites, and resources referenced in specific chapters and appendices of the manual. While hyperlinks are included in the chapters and appendices, readers will find a complete listing in Appendix XVII.

Children and Youth. For purposes of this manual, the term “child” refers to any individual who is not older than age 21 or is not yet at a grade level at which the local education agency provides a free public education as defined in section 1115(c)(1)(A) of ESEA, as amended, and 34 CFR § 200.103(a).[1] However, readers should be aware that the term “child” as it is used in the manual includes children, youth, and perhaps even young adults.

Recruiter. For purposes of this manual, the term “recruiter” refers to any individual who gathers facts for a determination of a child’s eligibility for the MEP.

1 Section 1304(c)(2) of the ESEA requires each SEA to implement its MEP program and projects in a manner consistent with the objectives of section 1115(b) and (d) of the ESEA. To be consistent with 1115(b) and (d), a MEP participant must also meet the eligibility requirements described in 1115(c)(1)(A) of the ESEA. ↑

Abbreviations

| AYP | Adequate Yearly Progress |

| BAM | Born After the Move |

| BMEI | Binational Migrant Education Initiative |

| CAMP | College Assistance Migrant Program |

| CAPTA | Child Abuse Protection and Treatment Act |

| CFR | Code of Federal Regulations |

| CHIP | Children’s Health Insurance Program |

| COE | Certificate of Eligibility |

| CNA | Comprehensive Needs Assessment |

| CSPR | Consolidated State Performance Report |

| DES | Data Entry Specialist |

| DOB | Date of Birth |

| ED | U.S. Department of Education |

| EL | English Learner |

| ELL | English Language Learner |

| ELP | English Language Proficient |

| ESL | English as a Second Language |

| EOE | End of Eligibility |

| ESEA | Elementary and Secondary Act of 1965, as amended |

| ESSA | Every Student Succeeds Act |

| FERPA | Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act |

| GED | General Equivalency Diploma |

| HEP | High School Equivalency Program |

| HRSA | U.S. Department of Health, Resources and Services Administration |

| HSE | High School Equivalency |

| HSED | High School Equivalency Diploma |

| ICE | Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

| ID&R | Identification and Recruitment |

| ID&R Manual | Migrant Education Program National ID&R Manual |

| IHE | Institute of Higher Education |

| INS | Immigration and Naturalization Service |

| LEA | Local Educational Agency |

| LOA | Local Operating Agency |

| MAW | Migratory Agricultural Worker |

| MF | Migratory Fisher |

| MEP | Migrant Education Program |

| MSIX | Migrant Student Information Exchange |

| MOU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| NASDME | National Association of State Directors of Migrant Education |

| NASS | National Agricultural Statistics Service |

| NAWS | National Agricultural Workers Survey |

| NFJP | National Farmworker Jobs Program |

| NIFA | National Institute of Food and Agriculture |

| NRG | Non-regulatory Guidance (MEP Guidance) |

| NSLP | National School Lunch Program |

| OCR | Office of Civil Rights |

| OIG | Office of the Inspector General |

| OME | Office of Migrant Education |

| OSY | Out-of-School Youth |

| PAC | Parent Advisory Council |

| QAD | Qualifying Arrival Date |

| QM | Qualifying Move |

| QW | Qualifying Work |

| SBP | School Breakfast Program |

| SCHIP | State Children’s Health Insurance Program |

| SDP | Service Delivery Plan |

| SEA | State Educational Agency |

| SEVIS | Student Exchange Visitor Information System |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| SSI | Supplemental Security Income |

| SSN | Social Security Number |

| TANF | Temporary Assistance for Needy Families |

| USC | United States Code |

| USCIS | U.S. Citizen & Immigration Services |

| USDA | U.S. Department of Agriculture |

| U.S. DHHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| U.S. DHS | U.S. Department of Homeland Security |

| U.S. DOJ | U.S. Department of Justice |

| U.S. DOL | U.S. Department of Labor |

| U.S. DoS | U.S. Department of State |

| WIC | Women, Infants, and Children Program |

Part 1: The Recruiter Manual

Chapter 1. Background and Overview of the Migrant Education Program

Chapter 1 Learning Objectives

| Chapter 1 Learning Objectives |

|---|

|

The recruiter will learn |

|

the common characteristics of migratory agricultural workers and migratory fishers; |

|

the purpose of the MEP; |

|

who is eligible to be recruited into the MEP; |

|

the importance of finding migratory children; |

|

how the MEP is organized; and |

|

how important the recruiter is to the ID&R process. |

Children of Migratory Farmworkers and Fishers

Pedro is in his second school this academic year; his family moved from Texas to Michigan to harvest cherries.

Nancy was a freshman in high school last year, but now she has left school to pick apples with her father.

Thelma dreams of being a nurse someday, but knows she’ll never have enough credits to graduate from high school because her family keeps moving back and forth from California to Oregon.

These are the children of America’s migratory workers, and their education suffers as a consequence of their family’s mobile way of life. The purpose of the MEP is to locate these children, determine whether they are eligible for the program, and, if so, provide them with the supplemental instructional and support services they need to succeed in school.

Our nation’s economy depends upon workers who perform a variety of temporary and seasonal jobs that help produce, harvest, and process crops, livestock, poultry, fish, shellfish, dairy, and other agricultural products. The workers who fill these jobs are often forced to piece together a number of agricultural or fishing jobs to make a living that will sustain them and their families throughout the year. These jobs are often located far from one another, requiring the worker to move and reside temporarily in an area near the work. Due to economic necessity, many workers and their families migrate back and forth from a home base[2] to locations where they can obtain one or more of these temporary or seasonal jobs. The workers who move in search of such work are known as “migratory” agricultural workers or fishers.

Migratory agricultural workers and fishers share a number of common characteristics that pose significant challenges in their lives:

- They repeatedly relocate for work due to economic necessity.

- They are often isolated from services.

- They are “working poor” as a result of the low wages they are paid for their labor.

- They often reside in sub-standard living conditions.

- They frequently have low levels of education.

- They are subject to inadequate or non-existent health care.

- They often feel isolated from the larger community because they come from a different culture and frequently speak a language other than English (some speak indigenous languages, making it difficult to find interpreters and translated materials).

- They often move to and from other countries (especially Mexico).

- Many live in fear due to documentation and legal status issues.

- These characteristics and life experiences create unique educational circumstances for the children of migratory workers and young migratory workers who move regularly.

- Migration means changing schools, teachers, and curricula, and often chronic absenteeism for school-age children. Changing schools diminishes a student’s sense of belonging and makes it more difficult to participate in the classroom and extracurricular activities.

- Children of migratory workers often have limited opportunities to learn the English language because their parents may not be proficient in English. Furthermore, children who spend part of the year in countries (and schools) in which English is not commonly spoken do not have as much opportunity to learn and practice English.

- Migratory parents’ low levels of education and socioeconomic status often limit the amount and quality of educational support that can be offered in the home.

- Health insurance and wages that ensure adequate access to health care for young children and adolescents are not generally provided by temporary and seasonal jobs in agriculture and fishing.

- Because they are temporary residents, migratory workers and their children are often treated like outsiders and may face discrimination. This fact may limit their access to services to which they are entitled.

- Students may not receive academic credit for courses they have completed when states do not have an active system for granting and transferring course credits earned within the state, or accepting course credits earned in other states.

Migratory children are known to be at high risk of school failure due to these characteristics and experiences. The unique educational needs that arise from the migratory lifestyle and the challenges our nation’s schools face in effectively educating a highly mobile and disadvantaged population keep that risk high.

Migratory out-of-school youth (OSY) who work in agriculture or fishing rather than attending school are at an even greater risk of failing to obtain the level of education required to succeed in life. These OSY may travel with families, an older relative or crew chief, in small groups, or alone. In the Consolidated State Performance Reports (CSPR) for 2014-2015, States identified 35,165 OSY eligible for services, which was 10.5 percent of the total population of migrant students identified as eligible for services (332,335) (ED, ED Data Express, 2014-2015). OSY face all of the obstacles to education encountered by other migratory students, plus additional challenges. OSY are seldom connected with the community in which they live, and as a result, the MEP may be their only link to education, support, and the medical services they need.

2 Many migratory families have a home base or hometown where they live for much of the year. They travel or migrate from this home base to other places to work. ↑

Purpose of the Migrant Education Program

In 1966, the U.S. Congress amended Title I of the ESEA to include a new section: Part C—Education of Migratory Children. Through this amendment Congress authorized, for the first time, a program that provided states with federal financial assistance to help improve the educational opportunities and academic success for the children of migratory agricultural workers. This program was called the Migrant Education Program, or MEP.

The ESEA, as amended by the ESSA, states that the purpose of the MEP is

- to assist states in supporting high-quality and comprehensive educational programs and services during the school year and, as applicable, during summer or intersession periods, that address the unique educational needs of migratory children;

- to ensure that migratory children who move among the states are not penalized in any manner by disparities among the states in curriculum, graduation requirements, challenging state academic standards;

- to ensure that migratory children receive full and appropriate opportunities to meet the same challenging state academic standards that all children are expected to meet;

- to help migratory children overcome educational disruption, cultural and language barriers, social isolation, various health-related problems, and other factors that inhibit the ability of such children to succeed in school;

- to help migratory children benefit from state and local systemic reforms. (Section 1301 of the ESEA, as amended)

The principal operational goal of the MEP is to ensure that all migratory students meet challenging academic standards so that they graduate with a high school diploma or receive a High School Equivalency Diploma (HSED) that prepares them for responsible citizenship, further learning, and productive employment.

Who is Eligible for the MEP?

The MEP was designed to help migratory children find success through education. Preparing a preschooler for kindergarten, helping a student learn to read or enhancing their English language proficiency, ensuring a child’s promotion to the next grade, and helping a high school student earn credits toward graduation are just a few examples of activities that the MEP supports. However, before the MEP can provide any services, MEP staff must determine that a child is eligible for the MEP. To understand migratory child eligibility, it is important to review the law.

According to sections 1115(c)(1)(A) (incorporated into the MEP by sections 1304(c)(2), 1115(b)), and 1309(3) of the ESEA, and 34 C.F.R. § 200.103(a)), a child is a "migratory child" if the following conditions are met:

- The child is not older than 21 years of age; and

- the child is entitled to a free public education (through grade 12) under state law, or

- the child is not yet at a grade level at which the LEA provides a free public education; and

- The child made a qualifying move in the preceding 36 months as a migratory agricultural worker or a migratory fisher, or did so with, or to join a parent/guardian or spouse who is a migratory agricultural worker or a migratory fisher; and

- With regard to the qualifying move identified in paragraph 3, above, the child moved due to economic necessity from one residence to another residence, and

- From one school district to another; or

- In a state that is comprised of a single school district, has moved from one administrative area to another with such district; or

- Resides in a school district of more than 15,000 square miles and migrates a distance of 20 miles or more to a temporary residence. (NRG, Ch. II, A1)

Note for the three terms defined in both the statue and program regulations (“migratory child,” “migratory agricultural worker,” and “migratory fisher”), the statutory definition in the ESEA, as amended by the ESSA, takes precedence. In addition, the term “in order to obtain” no longer appears in statute, and its definition in 34 CFR § 200.81(d) is therefore no longer applicable.

Children who fit the above definition are eligible for MEP services. However, only those children who are between the ages of three and 22 (i.e., have not had a 22nd birthday) are counted for state funding purposes.

The Importance of ID&R in Determining Eligibility for the MEP

Working for the MEP means you are affecting the lives of the nation’s most disadvantaged children. Without the MEP, no one would be looking out for these children.

Identification means actively looking for and finding migratory children and youth. Recruitment means making contact with the family or youth and obtaining the necessary information to document the student’s eligibility and enroll them into the MEP.

The ID&R of migratory children is essential because the SEA must create a record of eligibility for each migratory child before he or she can receive any of the MEP’s educational or supportive services. The longer it takes a state to find a migratory child, the more time passes before the child receives the extra services he or she needs to succeed. Furthermore, the children who are most in need of MEP services are often the most difficult to find. Migratory children who are not identified may experience problems such as delays in placement or incorrect school assignment; failure to count partial credits or inappropriate course sequence for graduation from the student’s home-based school; and obstacles to receiving necessary supplemental services. Even if an individual migratory child does not receive direct services, it is important to identify all migratory children so their needs can be assessed and monitored to plan future services if a need does arise.

Effective ID&R is a challenge for the MEP. The proper and timely ID&R of migratory children may be a difficult task for a number of reasons:

- Not all temporary or seasonal workers are eligible for the MEP because the worker must have moved due to economic necessity from one residence to another and from one school district to another and have (1) engaged in new qualifying work soon after the move, or (2) if the worker did not engage in new qualifying work soon after the move, actively sought such employment and had a history of moves for qualifying work. The eligibility requirements for the MEP require strong analytical skills to properly evaluate eligibility.

- Migratory families are inclined to be self-sufficient and are not accustomed to seeking help outside of their own circle of family and friends.

- Children of migratory workers are often invisible, quietly coming and going, and not attracting much attention in a new community. If these children are not actively recruited, many would not be in school (they may accompany their parents to work or be left alone at home) or receive services from the MEP.

- Finding and recruiting many OSY who travel without their families or in groups of OSY is especially challenging. The traditional in-school recruitment model is not feasible because this population has no contact with the school district. Recruitment of OSY is most successful when it occurs at work sites, in the field, and at businesses where these youth work, as well as in housing where they live.

- Migratory families often do not speak or read English or are English language learners (ELLs), and some are not literate in their native language.

- Frequently, there are significant cultural barriers and misunderstandings between the migratory family and the community in which they reside.

- The places where migratory families work and reside are often located in remote areas, and employers may be uncomfortable if their employees have outside visitors during the workday. Employers may also discourage outside visitors because of concerns about liability, productivity, or the legality of their workers.

- There is considerable turnover in migratory agricultural and fishing work. The work is often difficult, dangerous, and, under the best circumstances, results in only modest wages. Living conditions in farmworker camps and other temporary, poorly maintained housing can be hard on all of the family members. Yet, while many migratory workers move into easier and more stable employment, others remain in or re-enter the migratory labor pool because they view the temporary or seasonal work in agriculture or fishing as their only employment option in the workforce.

- The MEP may not be able to serve all migratory children; the children may not currently need supplemental academic help or they may not be deemed a priority for service. Therefore, some families may not see an immediate benefit to their child being identified and may forgo the process.

For these and other reasons, the MEP needs to employ trained staff to identify and recruit migratory children. These staff members are usually called “recruiters,” and they receive extensive training in a basic set of procedures on how to find and recruit migratory children for the MEP.

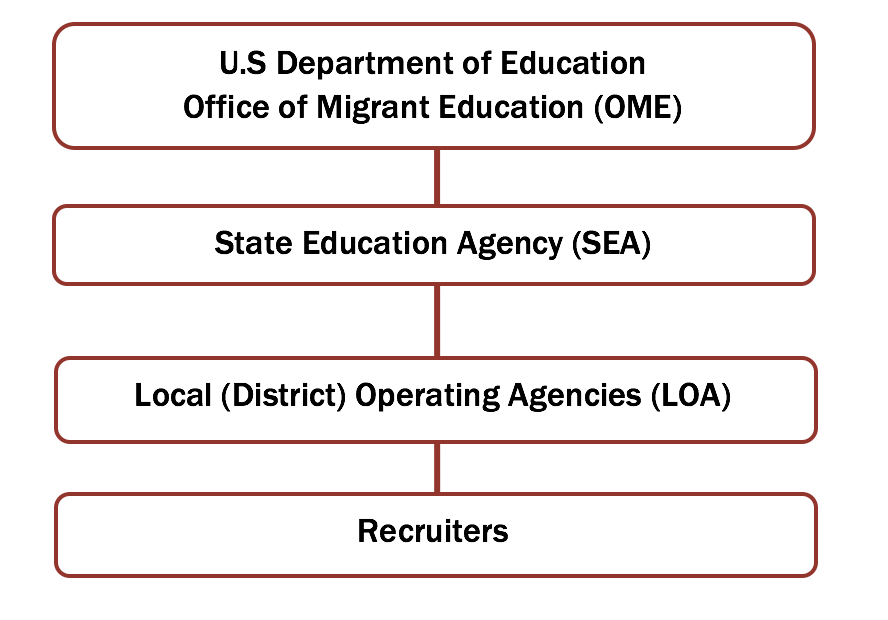

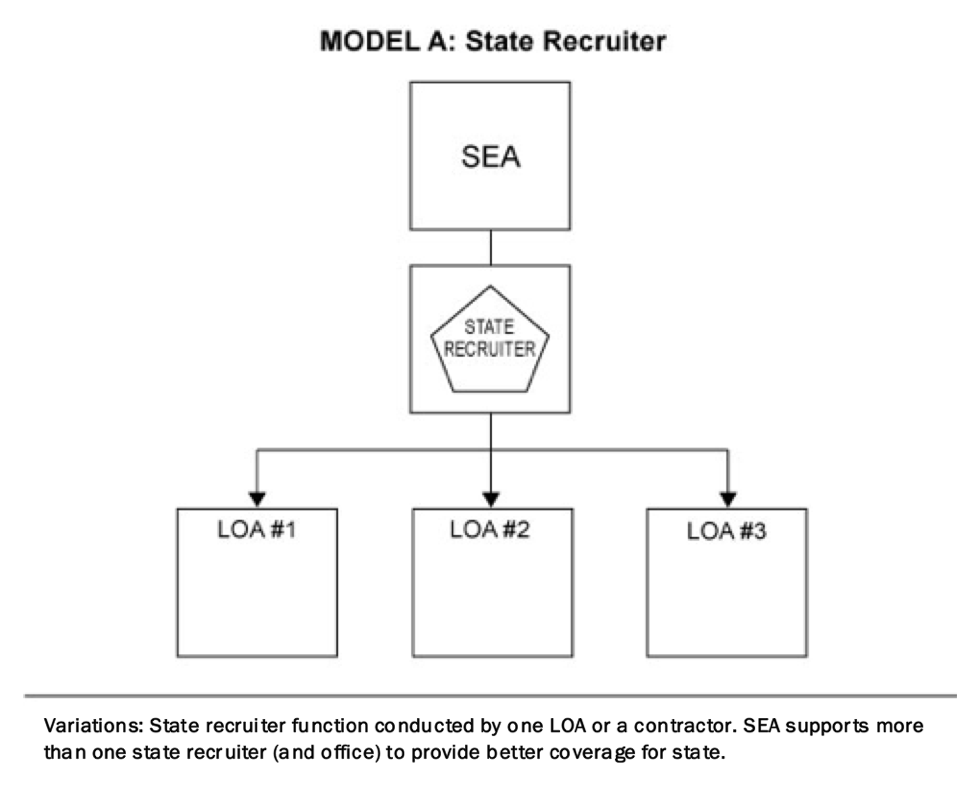

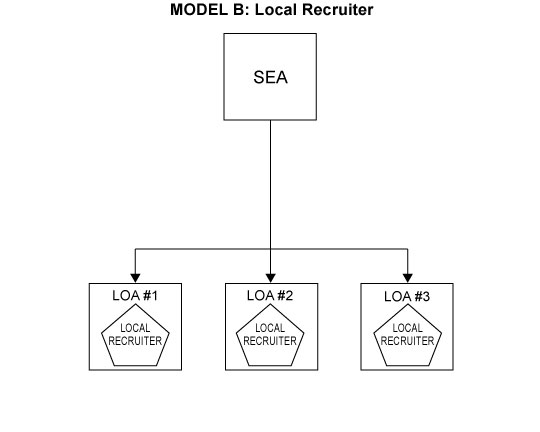

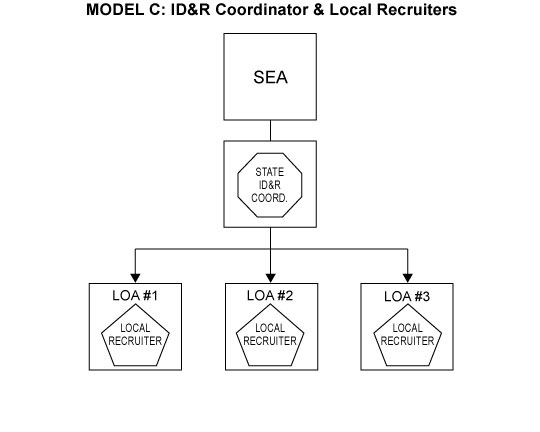

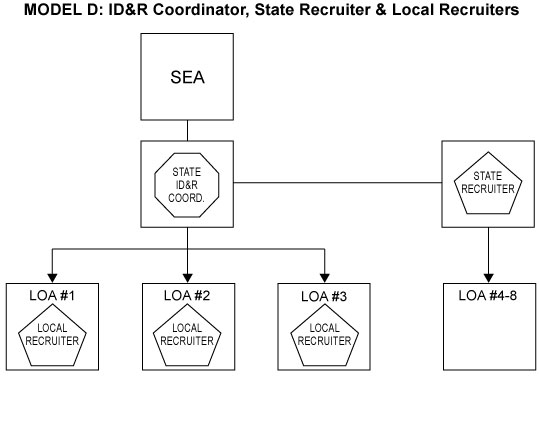

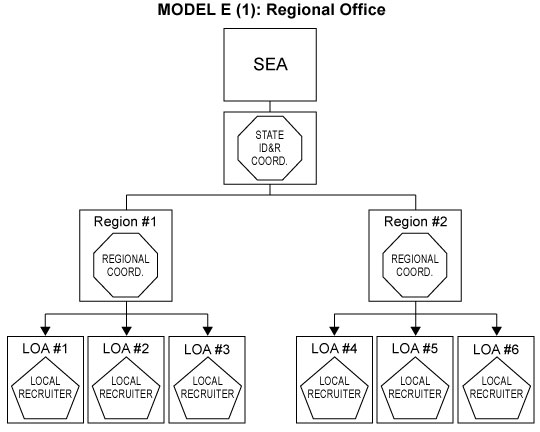

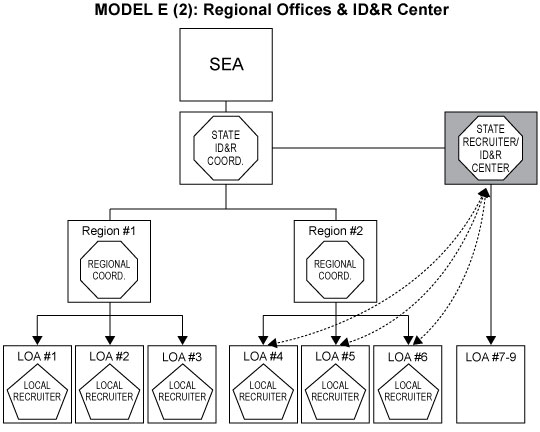

Organization of the MEP

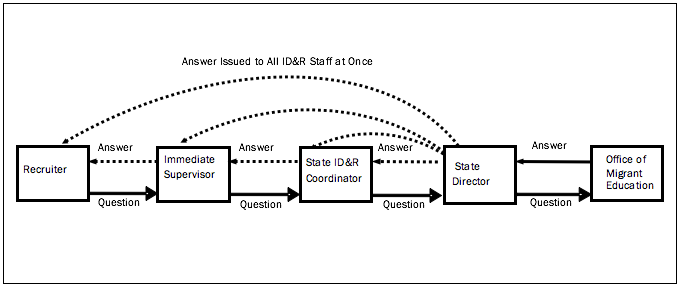

There are many state MEP organizational structures. An example of an MEP structure is found below in Figure 1. While the MEP is administered by a single office (OME) within ED, organizational structures below the federal level differ from state to state. Throughout the country, staff works on the MEP at the local, state, and federal levels.

Figure 1. A Typical MEP Organizational Structure

Role of Federal MEP Staff. OME administers the MEP nationally and provides guidance and support to SEAs that receive grants. The OME has several responsibilities, including providing national leadership, conducting special initiatives, helping ED to calculate state MEP allocations, monitoring state programs for compliance with federal requirements, collecting and analyzing student performance data, developing regulations and guidance, and providing technical assistance on how to implement the MEP. A federal program officer (i.e., contact person) is assigned to each state to assist and monitor its implementation of the MEP.

The OME has developed Non-Regulatory Guidance (NRG), a policy document that is written in an easy-to-follow question-and-answer format to help SEAs and LOAs understand the requirements that apply to the MEP and to suggest ways to implement them. As statutory or regulatory requirements change, OME updates the NRG to help clarify the policies as they relate to the MEP. Recruiters are strongly encouraged to study the Chapters II and III of the NRG on “Child Eligibility” and “Identification and Recruitment.”

Role of State MEP Staff. ED awards MEP formula grants to SEAs, which are solely responsible for the operation and administration of the program; most SEAs subgrant a portion of their MEP grant to LOAs, which help SEAs administer and operate the program. At the state level, most states have a MEP Director who is responsible for overseeing all aspects of the administration of the program, including the state’s ID&R system. The MEP Director may also have program responsibilities for other federal programs. The focus of the state MEP Director is to provide overall leadership and direction for the state as a whole, and to ensure that local programs comply with all applicable laws and other requirements. The state is responsible for finding and enrolling migratory children from across the state, for determining their unique needs, and for developing a service delivery plan that uses resources in an equitable and effective manner. Most states also have ID&R Coordinators who provide statewide leadership and guidance to recruiters. When a recruiter asks a question that cannot be answered at the local level, the recruiter should raise the question at the state level for a response. It is important to recognize that each state has its own policies and procedures regarding chain-of-command and how to address questions and concerns. The recruiter should check with an immediate supervisor to learn the protocols in his or her state.

Role of Local MEP Staff. At the LOA level, the emphasis is on finding and serving individual migratory children. The recruiter, perhaps with assistance from other local staff, finds migratory children, determines whether they are eligible for the MEP, and helps connect them with appropriate services. Once the child is identified and the child’s needs are assessed, educators and others at the district level who serve migratory children may provide extra services that are beyond those offered by the local school. For example, MEP teachers and tutors may provide in-home tutoring, after school coursework, or summer programs. Migratory children may also be eligible to receive services through other programs serving migratory students, such as

- The High School Equivalency Program (HEP), under which ED provides competitive grants to colleges, universities and non-profit organizations to help migratory and seasonal farmworkers and their immediate family members who are 16 years of age or older to obtain a HSED certificate or equivalent to gain employment, enter postsecondary education, or the military.

- The College Assistance Migrant Program (CAMP), under which ED provides competitive grants help migratory and seasonal farmworkers and their immediate family members complete their first undergraduate year of study in a college or university.

Local school districts that receive a subgrant from the SEA to serve migratory children are responsible to the state MEP. When a recruiter or anyone else at the local level has a question or needs support, the recruiter should turn to an immediate supervisor for assistance. The supervisor may be an ID&R staff member or a local program coordinator who has broader duties. Local projects are often asked to gather local data for the state for evaluation purposes and also to inform state decision makers.

Conclusion

The MEP helps meet the academic needs of an important and often overlooked sector of our society: migratory children. If it were not for the efforts of the MEP at the local, state, and federal levels, migratory children might remain invisible. In many cases, migratory children would not be identified or served if MEPs did not employ a network of recruiters to find and enroll them into the program. Without a record of eligibility, these children would not be able to receive the additional services they need to be successful. There are many layers of support at the local, state and federal levels of the MEP, so the recruiter should never feel that he or she is alone.

Chapter 2. The MEP Recruiter

Chapter 2 Learning Objectives

| Chapter 2 Learning Objectives |

|---|

|

The recruiter will learn |

|

the characteristics of a successful recruiter; |

|

the recruiter’s basic duties and responsibilities; |

|

how personal emotions can affect the recruiter’s behavior toward needy families and youth; |

|

the importance of knowing what services the recruiter’s local MEP provides; and |

|

that recruitment is a team effort. |

Recruitment Duties and Responsibilities

A good recruiter is determined more by his or her aptitude and attitude toward performing the unique responsibilities of the job than by any formal educational process.

Recruiters are very important because they often serve as the first contact between a migratory family or youth and the local school district, as well as the community at large. Also, for OSY, the recruiter may be the first direct contact with someone outside of their work crew. The initial contact is crucial because it provides the recruiter with the opportunity to determine whether the child may be eligible for the MEP. During this visit, the recruiter also sets the tone for the home-school relationship. It is the responsibility of the recruiter to be helpful without allowing the family or youth to become overly dependent on his/her assistance. The recruiter is often considered an ambassador in the eyes of migratory parents, the school district, agricultural employers, and the community. For example, a bilingual recruiter may be instrumental in explaining important school policies to a migratory family and may be an important connection for an OSY to educational and social service opportunities. In this way, the recruiter is the main link between the migratory family or youth and the MEP and other resources.

The recruiter’s primary job is to find and enroll eligible migratory children into the MEP. Locating migratory children can be hard work, and the recruiter must become skilled at performing a range of duties and adapting to situations to be successful. While recruiting migratory children is the recruiter’s primary responsibility, he or she also often plays an important role in helping to ensure that these children receive vital educational and social services. Thus, while “recruiter” is the most commonly used term to describe this staff position, other terms used include

- advocate

- home visitor

- recruitment specialist

- interviewer

- school liaison

- community liaison

- outreach worker

The MEP recruiter’s primary responsibilities include the following:

- learning the MEP eligibility requirements

- establishing and maintaining a recruitment network

- becoming familiar with locations where migratory families and youth live and work

- finding migratory children and their families and youth

- explaining the MEP to migratory families and youth

- interviewing migratory families and youth

- making preliminary determinations on the eligibility of the child and youth

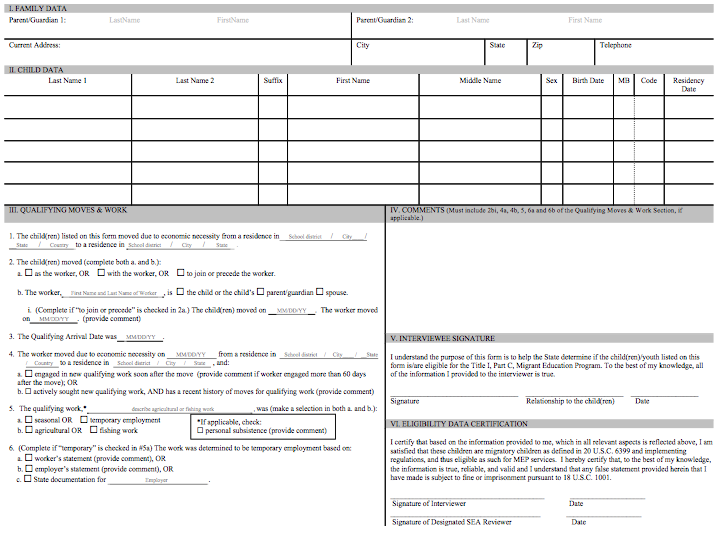

- completing the Certificate of Eligibility (COE)

- collecting child eligibility and other basic program data

- implementing state quality control procedures

- following ethical standards and confidentiality laws

- facilitating communication among migratory families, schools, agricultural

employers, and the community

The recruiter often has job responsibilities beyond ID&R. For example, the recruiter may help migratory families navigate the unfamiliar, and sometimes unfriendly, environment that families might encounter in a new community. As mentioned previously, the recruiter may also work as an advocate, translator, home-school liaison, or parent involvement coordinator.

Characteristics of a Successful Recruiter

Great recruiters are made, not born. If a recruiter doesn’t feel ready to do the job, the recruiter should work with a supervisor to identify and develop the skills needed to be successful.

Experienced ID&R coordinators say that, as a general rule, it takes about three years for a recruiter to fully learn the job. The specific skills required to be a great recruiter are developed over time using strategies such as those described in Chapter 3. If the recruiter does not initially possess these skills, the supervisor can help the recruiter cultivate them.

When ID&R coordinators and MEP administrators are asked about “a great recruiter” or “their best recruiter,” certain characteristics emerge. A great recruiter is able to

- make correct eligibility decisions,

- document child eligibility accurately and clearly,

- manage time wisely,

- work independently,

- remain flexible and adapt to a constantly changing environment,

- relate well to others and gain their trust,

- create positive relationships with agricultural employers,

- use effective interviewing (i.e., questioning) skills,

- maintain appropriate relationship boundaries,

- follow confidentiality laws,

- demonstrate personal integrity, and

- speak local migratory families’ native language and exhibit cultural sensitivity.

Few recruiters come to the job with all of the skills that make a great recruiter. Effort, enthusiasm, and a willingness to learn are necessary. Although it may take a number of years to be considered great, it is within the grasp of every recruiter to achieve excellence.

Lessons Learned: Recruiter Roles & Responsibilities

Each recruiter has stories about things that went wrong or that could have been done differently in carrying out his or her roles and responsibilities. These lessons learned may help the new recruiter avoid pitfalls that experienced recruiters have faced.

Know About the Local MEP. The recruiter must know more than just recruitment. As stated earlier, the recruiter is often the face of the MEP to families, OSY, schools, and the local community. A recruiter is also a champion for the MEP. A migratory family will often ask the recruiter questions about MEP services that the school and other programs offer, such as does the MEP offer a pre-school program, is there a summer school, are dropouts eligible for the MEP, and what programs are available to help my son/daughter graduate? The recruiter should learn about the MEP and other school and community programs that migratory children and families are eligible to receive.

Develop A Recruitment Network. A recruitment network is a system of contacts, including individuals, agencies, and other institutions, that provide information on how to identify and locate potentially eligible children. Establishing a recruitment network and developing a strong working relationship with each member of that network is an important way of finding migratory children who may be eligible for MEP services. When done properly, a recruitment network can serve as the eyes and ears of the recruiter. Key sources of information include employers, schools, community-based agencies, commercial establishments, and others. The recruitment network is further explained in Chapters 4 and 5.

Determine Work Priorities. The recruiter often has many roles. If the recruiter is expected to recruit and do other work for the MEP, the recruiter should determine the work the supervisor considers the highest priority and allocate time accordingly. For example, the recruiter, with guidance from the supervisor, may need to decide which of the following activities would be most productive: attending a job fair to recruit, staying in the school’s main office to meet new families that may be eligible for the MEP, knocking on doors to canvass for new families, or translating at the MEP after-school program. In order to prioritize, the recruiter will need to assess which of these activities provide the greatest benefit to the MEP.

Give the MEP Its Due. If a recruiter is paid by more than one funding source, the recruiter should ask an immediate supervisor how much of his or her time is paid from MEP funds and how many hours per week should be spent on ID&R activities. The recruiter should then devote that amount of time to MEP work. If the school asks the recruiter to spend MEP time on work that does not directly benefit the MEP (e.g., playground or lunchroom duty or translating for non-migratory parents), the recruiter should respectfully decline. If the school insists that the recruiter spend MEP-funded time on non-MEP work, the recruiter should contact a supervisor. Similarly, a recruiter who works full-time for the MEP should guard his or her time to make sure all work activities benefit the MEP.

Ask Questions. There are many people who work in the MEP who are willing to help the recruiter do the job correctly. If the recruiter has a question or does not understand how something should be done, the recruiter should ask someone who is knowledgeable and write down the answer. In this way, the recruiter will become increasingly knowledgeable over time.

Make Ethical Decisions. The recruiter will meet families and youth who have great needs. The recruiter may believe that those children need and deserve help, even if they do not qualify for the MEP. On the other hand, the recruiter may meet families whose children clearly qualify for the MEP, but may not find them as deserving. Because of these feelings, the recruiter may experience internal conflict about making accurate eligibility decisions. Each recruiter brings a set of personal beliefs and biases to the job; the recruiter will need to put these personal feelings aside in order to make objective decisions based on the MEP eligibility criteria.

Maintain Appropriate Relationship Boundaries. The needs of migratory families can be overwhelming to a recruiter. However, it is important for a recruiter not to make promises that cannot be kept. The recruiter should exercise caution in assisting needy families and youth with non-educationally related needs. Good judgment and tact must be used in deciding when and for how long to help a family. For example, a migratory family that has recently arrived from another country is often more dependent on the recruiter’s guidance, assistance, and support than a family who has spent more time in the U.S. The bilingual recruiter may be the only one who can make a school appointment for a family, help the family resolve an unpaid medical bill, or direct the family to other services in the community. However, there is a fine line between providing support to a family and hindering the family’s ability to become self-reliant. The recruiter should learn when it is appropriate to help a family and when to refer the family to other local services. The best service a recruiter can provide migratory families or youth is to help them develop skills that will enable them to become increasingly independent.

Be Aware of Federal, State and Local Requirements. States and LOAs may have their own requirements for the recruiter that go beyond the federal requirements. For example, if the vast majority of migratory families are of Mexican origin, a state may require the recruiter to know Spanish and demonstrate sensitivity to the various cultures of Mexico. Other state-specific requirements may include responsibility for knowing and understanding privacy laws and reporting suspected cases of child abuse or child abduction. Recruiters also need to become familiar with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the federal law that protects the privacy of student education records from unauthorized release. While these areas should be part of every recruiter’s training, if the recruiter is not aware of FERPA or the applicable state privacy, child abuse, or other relevant laws, the recruiter should ask a supervisor.

Volunteers Expand Services. A well-established volunteer network can provide recruiters with resources outside of the realm of MEP funding and can be called into action when a recruiter is feeling overwhelmed with service requests. Despite assumptions to the contrary, many people are interested in assisting the migratory community—churches, students at institutions of higher learning, retirees, community members, and various coalitions frequently seek a fulfilling volunteer experience. A recruiter’s impact can increase exponentially when working in collaboration with a strong volunteer network.

Remember That a Recruiter Is Not Alone. Being a recruiter can sometimes seem like a lonely job. However, ID&R is a team effort. It is important for the recruiter to understand that identifying, recruiting, and determining the eligibility of migratory children is the mutual responsibility of the recruiter and the ID&R team. When the recruiter has questions or needs help, there are other people who work in the MEP at the local, state, and federal levels who can assist. For example, local program staff may be able to provide leads on children who may be eligible for the MEP, a recruitment supervisor may help in planning recruitment strategies, and state staff may be able to assist in resolving eligibility questions. Spending a day in the field shadowing a fellow recruiter can also be beneficial to learn new recruiting techniques and get a different perspective from another person who understands the challenges facing recruiters.

Conclusion

Reaching migratory children and youth is at the heart of the MEP, and the importance of effective recruitment cannot be overemphasized. Without a good recruiter, the neediest migratory children may not be served. The effective recruiter can become the center of a network that connects migratory families and youth to schools and communities. When migratory families trust the recruiter, they are much more likely to tell him or her when new migratory families move into an area. When growers and other employers trust the recruiter, they are more likely to allow recruitment at the employment site and to support the MEP. Recognizing the value of these networks is the beginning of great recruiting. Chapter 3 will discuss how the recruiter learns the job.

Chapter 3. Learning to Recruit

Chapter 3 Learning Objectives

| Chapter 3 Learning Objectives |

|---|

|

The recruiter will learn |

|

that each state has its own requirements for basic training; and |

|

multiple strategies for building their skills as a recruiter, including |

|

becoming familiar with the NRG; |

|

reviewing the knowledge and skills needed to identify and recruit migratory children; |

|

meeting with his or her supervisor to ask questions, particularly on child eligibility; |

|

conducting a “self-check” of whether he or she understands MEP child eligibility or passing a state certification exam or knowledge check where required; |

|

finding a knowledgeable mentor; |

|

observing one or more experienced recruiters interview a migratory parent or youth; |

|

determining on what topics he or she needs more training and request it; |

|

identifying other recruiters to share ideas; |

|

arranging to be observed by his or her supervisor; |

|

finding out where to go to ask questions; and |

|

providing feedback on ways the training can be improved. |

Learning about Identification and Recruitment

To successfully find migratory children, the recruiter must have a clear idea of who to look for and the best strategies for finding them. Training both novice and veteran recruiters can be compared to teaching someone to drive a car. Just as a driver education instructor would not put a new student driver behind the wheel of a car on a busy road, those who administer the MEP at a state or local level should not send a new recruiter out to find and interview migratory families or youth without proper instruction and guided practice. Similarly, veteran recruiters, like veteran drivers, may need a defensive driving course once in a while to refresh their knowledge and skills.

The process that a new driver goes through to learn the “rules of the road” is similar to the process that a new recruiter goes through to learn the basic MEP child eligibility requirements. Learning the rules of the road generally involves both classroom instruction and independent study, as does learning basic MEP eligibility definitions. Likewise, the guided practice that a new driver receives with the help of a driver education instructor or parent is similar to what the new recruiter should receive under a knowledgeable and experienced recruitment mentor. Finally, before a new driver may operate a car alone, he or she must pass a driver’s test. Along the same lines, the new recruiter should demonstrate proficiency in recruiting eligible children before being allowed to work independently. Some states require the new recruiter to take a certification examination or survey that measures the recruiter’s ability to make correct eligibility determinations.

Furthermore, state and local personnel should not assume that veteran recruiters do not need continual training and development. As in some states, where drivers may have to take a vision test or a road test to renew their license, veteran recruiters will need to retrain and relearn as laws and regulations change. Beyond new laws and regulatory changes, veteran recruiters should seek out at least one professional development opportunity a year to enhance skills and knowledge.

The recruiter and an immediate supervisor should work together to build and maintain the recruiter’s knowledge and skills. This chapter will discuss the general knowledge and skills of ID&R, the types of training a recruiter might receive, and other strategies to help the recruiter learn, or relearn, the job of ID&R.

Knowledge and Skills of Identification and Recruitment

OME has developed the National ID&R Curriculum that identifies the core knowledge and skills that it believes a recruiter needs to master in order to properly identify and recruit migratory children and make preliminary eligibility determinations.

The National ID&R Curriculum consists of eight modules, each based on one or more chapters of the National ID&R Manual. The content of each module is taught through research-based instructional strategies designed to meet the needs of all learners. Participants will use the four modalities of recruiting (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) to process the content being delivered, and the trainer will facilitate the learning process by actively monitoring, questioning, and clarifying, when needed.

Each module consists of 1-3 levels designed to allow the trainer the option of selecting specific topics to train based on the composition of the audience. Level 1 will provide the basic information for the module topic, which makes it ideal for new recruiters and/or MEP staff members to use as a refresher for veteran recruiters. Subsequent levels provide additional topics of study related to the module, which make them ideal for follow-up or in-depth trainings.

The National ID&R Curriculum was created to transform the National ID&R Manual’s set of knowledge and skills into a training experience The curriculum is based on the following five objectives:

- State and local MEP recruiters understand the background of the MEP, the ID&R process of the MEP, and the duties and responsibilities of a recruiter. As indicated by this first objective, the recruiter will learn about the purpose, basic history, and organization of the MEP. In addition, the recruiter will learn the basic eligibility requirements and the general process for ID&R. Finally, the recruiter will become aware of his or her basic duties and responsibilities.

- State and local MEP personnel implement practices that result in the efficient ID&R of migratory children. To satisfy the second objective, the recruiter will learn how to develop a recruitment network, how to determine where migratory families and youth live and work, and how to locate them. The recruiter will also learn to understand and respect the diversity of migratory children, youth, and their families in order to interact with them effectively. The recruiter will practice how to explain the MEP to migratory families and youth and will learn how to organize and manage his or her caseload. Finally, the recruiter will learn how to take appropriate precautions to ensure personal safety.

- State and local MEP personnel implement practices that result in reliable and valid child eligibility determinations. For this third objective, the recruiter will master the child eligibility requirements under the MEP. The recruiter will also demonstrate the knowledge and skills needed to effectively interview a family or youth. The recruiter will learn to make valid and reliable preliminary child eligibility determinations and to implement quality control activities.

- State and local MEP personnel are aware of and adhere to ethical standards of behavior in child eligibility determinations. The recruiter will practice ethical behavior when determining a child’s eligibility.

- State and local MEP personnel implement practices that strengthen coordination and collaboration between migratory families, schools, and the community. The recruiter will demonstrate the ability to facilitate coordination and collaboration between migratory families, schools, and the community. The recruiter will practice meeting planning, facilitation, and team building.

States may want to consider developing their own ID&R training programs that are customized to the specific needs and characteristics of their states. For example, the recruiter should know about the local MEP including services offered, dates of operation, hours, and contact information. Here are some other topics that state and local training programs should consider, including

- how the state and local ID&R system is organized, including reporting relationships;

- state and local ID&R policies and procedures, including required paperwork;

- the content of the state and local ID&R plans, when available;

- demographic information regarding the characteristics of local migratory agricultural workers and fishers and their children, as well as their mobility patterns;

- state methods of collecting and maintaining data on migratory children;

- the recruiter’s role in the state’s quality control process and how to assist in developing and implementing the state or local plan for quality control, such as the mandatory federal re-interviewing requirements; and

- the organizations with which the SEA and LEAs expect the recruiter to coordinate and the amount of time the recruiter should allocate to this coordination.

The National ID&R Curriculum provides a structure that can be used to teach the newest recruiter the basic knowledge and skills needed to properly identify and recruit migratory children. It can also provide the most veteran recruiter with an understanding of more advanced recruitment concepts that prepares the recruiter for a stronger leadership role in the MEP. In combination with the National ID&R Curriculum, an individual state ID&R orientation, on-going training, and the National ID&R Manual, recruiters will discover the wide range of knowledge and skills necessary to become an effective MEP recruiter. States should continually work to improve their overall ID&R system and sharpen the knowledge and skills of new and veteran recruiters alike.

New Recruiter Training

The new recruiter generally receives basic training from an ID&R coordinator, a state-approved trainer, a local program coordinator, and/or a highly knowledgeable and skilled recruiter. This training often starts in a classroom or one-on-one setting and is generally followed by independent study and on-the-job training in the field. The on-the-job training often pairs the new recruiter with a highly skilled staff member until the new recruiter is ready to recruit or conduct an interview alone.

Classroom or Individual Training. By the end of the basic training, the recruiter should be able to correctly answer questions such as

- Why are migratory children identified and recruited? See Chapter 1.

- Who is eligible for the MEP? See Chapter 7.

- How do I find eligible children and youth? How do I develop an ID&R action plan? See Chapter 4, Chapter 5, and Appendix II.

- How do I conduct an interview? How do I explain the MEP to the family? What local services are available? See Chapter 6.

- How do I determine if a particular child is eligible for the MEP? See Chapter 7.

- What do I do if I encounter a situation that is not covered in the Sample Interview Script? See Chapter 6.

- How do I fill out a COE? See Chapter 8.

- How is my state’s student eligibility data collected, used, and stored? See Chapter 8.

- What ethical standards should I follow? See Chapter 2, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, and Chapter 8.

- What should I know about the language and culture of migratory families in my area? See Chapter 1.

- What safety precautions should I take when recruiting? See Chapter 5.

- What state and local laws should I know about? See state ID&R material.

After the classroom or individual training ends, the new recruiter should work with a supervisor to explore what other federal, state, and local training materials and opportunities are available, and use this information to develop a long-term personal training and development plan. SEAs and LOAs generally offer training on the MEP that recruiters are required to attend, and SEAs also hold an annual national ID&R conference that features workshops with updated ID&R information and methods. Even though not all recruiters may be able to attend a national MEP conference, the state and local staff generally obtain and disseminate information from the conference.

Independent Study. In addition to taking the basic classroom training, the recruiter should study key documents on his or her own. In particular, the new recruiter is encouraged to study the materials provided in the initial training, use the National ID&R Curriculum as a way to gauge progress in learning the suggested knowledge and skills, self-check through a review of the learning objectives listed at the beginning of each chapter and the use of the chapter checklists provided in Appendix XIIl, and carefully read and study relevant documents, such as

- the law and regulations (including the instructions to complete the National COE);

- the NRG;

- the National ID&R Manual;

- state ID&R materials (if available);

- the State’s Comprehensive Needs Assessment (CNA) and Comprehensive State Plan, also known as the Service Delivery Plan (SDP);

- applicable state and local laws, regulations, and policy guidance;

- relevant state and local ID&R action plans (more information will be provided in Chapter 5); and

- the RESULTS website (https://results.ed.gov).

The goal of independent study is for the new recruiter to become familiar with these key documents and resources and to know where to find answers to basic questions about ID&R and child eligibility. It is critical for the recruiter to stay up-to-date on the latest changes in guidance and policy at both the state and federal levels.

If you’re a new recruiter, find a good, experienced recruiter and ask if you can tag along when he or she makes home visits. After a few visits, attempt your first MEP introduction or conduct a parent interview. You’ll learn far more seeing it done and doing it than you will just talking about it or reading an ID&R manual. You might try this even if you are not a new recruiter. The really great recruiter is always trying to learn new things.

Field-Based Training. Many states try to match new recruiters with mentors who are highly knowledgeable and skilled. At first, the new recruiter will shadow the mentor on recruitment visits to observe how to conduct an eligibility interview. The new recruiter should observe how the mentor makes the initial contact, explains the MEP, conducts an interview (paying particular attention to what questions are asked to determine whether the child is eligible for the MEP), and handles questions, problems, or concerns that arise. After each visit, the mentor and new recruiter should debrief and discuss the interview and eligibility determination. The new recruiter may find it helpful to shadow several mentor recruiters to observe the different strengths of each.

After watching several interviews, the new recruiter should begin to conduct a small part of the interview with the mentor’s guidance. Each time the new recruiter conducts a part of an interview, the recruiter should talk with the mentor about how the interview went and ask the mentor for feedback or advice on how to improve for the next interview. This conversation should be away from the family or youth that was interviewed. As the new recruiter’s interviewing skills improve, he or she can take over more of the interview process until comfortable conducting a full interview. By the end of the peer-mentoring portion of the training, the recruiter should be able to properly conduct an interview, determine child eligibility, complete a COE form, and perform other key duties.

Sometimes, especially in small states and very isolated areas, mentoring may not be practical. In this case, the recruiter should try to practice interviewing through a role-playing exercise during the classroom training, perhaps with another new recruiter. Practice is important as it makes the actual interview flow naturally and helps to ensure that the recruiter collects all of the required information to complete the COE and make the preliminary eligibility determination. In situations like this, the recruiter should discuss with his or her supervisor other ways to obtain adequate training and/or mentoring opportunities, including contacting a nearby state able to send an experienced recruiter for a limited time (three to four days).

Some states require the recruiter to pass a certification exam or answer questions to demonstrate the recruiter’s knowledge of child eligibility requirements. The purpose of these tests is to assess whether the new recruiter fully understands program eligibility requirements and can apply them to determine if a child is eligible for the MEP. If the recruiter’s state does not have a certification exam or knowledge check, the recruiter should conduct a self-check to test how thoroughly he or she understands the MEP child eligibility requirements (see Appendix IX). If the recruiter does not pass the certification exam or knowledge check, the recruiter should talk with an immediate supervisor to find out which topics to study and arrange for further training.

On-the-Job Training

Learning how to recruit properly is a process that does not end when the recruiter has finished the training activities. The recruiter will continue to learn as he or she identifies and recruits migratory children. It is important for the recruiter to ask questions about any eligibility situation that is unclear and to seek direction and guidance from supervisors and peers to become highly knowledgeable and skilled.

Regular Meetings with the Supervisor. The new recruiter should meet regularly with the immediate supervisor to discuss child eligibility questions and other concerns that arise. Ideally, a supervisor will provide regular feedback during the training process; however, it is equally important for the recruiter to ask for regular feedback on whether he or she is properly applying the child eligibility requirements. This is vital during the first few months on the job to prevent any misunderstandings from becoming ingrained.

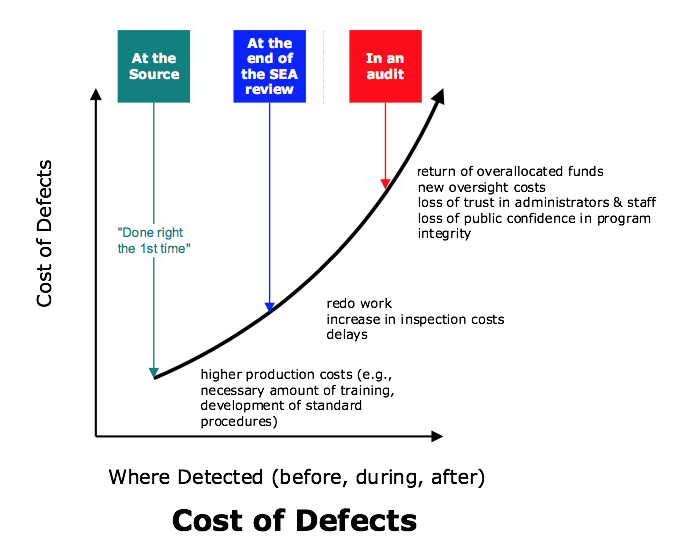

Performance Assessments by Supervisors. As part of the system of state quality controls, SEAs or LOAs are required to complete an annual review and evaluation of ID&R practices of individual recruiters [34 CFR § 200.89(d)(2)]. While supervisors may conduct a performance review with seasoned recruiters in an office setting, supervisors generally observe each new recruiter in the field. This allows a supervisor to provide comprehensive feedback on the recruiter’s rapport building, interviewing, decision-making, and documenting skills. The purpose of this observation is for the supervisor to see how the new recruiter approaches interviewing migratory families and making and documenting preliminary eligibility determinations. It is imperative that supervisors schedule observations with new recruiters. The recruiter should also request feedback on completed COEs to make sure they are being done properly.

Regular meetings and performance assessments also present an opportunity for the new recruiter to suggest ways of improving local ID&R efforts and to identify any training and development activities that would increase productivity. Suggestions from a new recruiter can be particularly useful to the supervisor because a new recruiter will view the system with fresh eyes and may be able to identify productivity solutions that are invisible to those who are comfortable with the process.

Recruiter Support System. The new recruiter should develop a network of other recruiters locally, regionally, or even nationally with whom to share tips and discuss problems. Recruiting can be stressful work; it is important to create a safe learning environment in which the recruiter feels free to share experiences and to learn from successes and failures. The recruiter may find it useful to work with mentors, peers, and the recruitment network to develop an individual ID&R action plan or to adapt an existing plan (more information on ID&R plans is provided in Chapter 5). The recruiter is encouraged to try promising new ID&R strategies and to share the results (both good and bad) with peers.

The recruiter may find it helpful to go on recruitment visits with outreach workers from other programs or agencies. For example, a recruiter may wish to join outreach staff from the National Farmworker Jobs Program (NFJP), administered by the U.S. Department of Labor, to learn how they approach migratory families and to learn more about the services they provide (more information on other agencies and organizations that provide services to farmworkers and their families is found in Appendix II).

Advanced Training and Ongoing Professional Development

The law that authorizes the MEP is updated generally every six to eight years. When the law is updated, ED will issue updated MEP regulations and guidance. Periodically, there are changes to other federal and state laws that affect migratory families as well, such as immigration or privacy laws. To properly identify and recruit migratory children, the recruiter must keep up with changes in the law, regulations, and guidance that affect the eligibility of migratory children (more information on other laws that may affect migratory families is found in Appendix I). The recruiter should also periodically visit the MEP web page at the U.S. Department of Education (https://oese.ed.gov/offices/office-of-migrant-education/migrant-education-program/) and the RESULTS website (https://results.ed.gov) for updates and resources. Keep in mind that the recruiter should initially attend his or her state MEP’s training and review state informational resources for MEP program changes and updates before going to the federal level.

To stay current, the recruiter should participate in advanced child eligibility training and ongoing professional development to continually update and improve needed knowledge and skills. The recruiter should make a point of attending local, regional, statewide, and national trainings when possible. Regardless of years of experience, recruiters and supervisors who do not participate in ongoing eligibility training are more likely to make mistakes when making child eligibility determinations than those who are trained regularly. In particular, experienced recruiters may be tempted to apply policies that were learned as new recruiters out of habit, even though those policies may be out-of-date. Timely training and regular meetings can help experienced recruiters overcome these old habits. Some questions a recruiter may want to answer after going through advanced eligibility training include

- Have any changes been made to the child eligibility requirements for the MEP? If so, what are they?

- How do I determine child eligibility in difficult cases?

- How can I strengthen my recruitment network?

- How can I improve my interviewing skills?

- What common mistakes have recruiters made in determining child eligibility and/or filling out COEs and how can I avoid making those mistakes?

- What ethical dilemmas could I encounter and how do I handle them?

- How are these and other recent changes reflected in my district, region, or state?

The recruiter, with the supervisor’s approval, may also want to explore professional development opportunities in other relevant areas, such as education reform, the language and culture of local migratory families, transient populations, negotiation skills, dealing with difficult people, public speaking, immigration issues, agricultural issues, time management, stress management, and safety and emergency training. The recruiter can check the listings at local universities, colleges, community centers, and other organizations for relevant course offerings and training.

In addition to training offered by the state, OME hosts an annual conference in which the latest information on MEP-specific issues, including eligibility and recruitment topics, is presented. It is important to note that not all states have the same policies and practices; therefore, it is crucial that conference participants check with their state or local administrators before implementing policies or practices presented at the OME Conference. Information on the conference can be obtained from the RESULTS website (https://results.ed.gov). In addition, there are regional, state, and national conferences, trainings, workshops, and meetings that include sessions and information on ID&R.

Conclusion

There are a number of ways in which the recruiter can learn the job of ID&R: participating in a new recruiter training program, studying the NRG and other key resources, working with a mentor, meeting regularly with a supervisor, and developing a support system. Having knowledgeable and well-trained recruiters is an ongoing responsibility of both the individual recruiter and the MEP administrator. Regardless of what training opportunities are available, it is the recruiter’s job to work with the supervisor to learn the MEP child eligibility requirements and to ask the supervisor for help when questions arise on whether a child qualifies for the MEP. Remember, regardless of the size of the migratory student population, and whether the recruiter’s position is full-time or part-time, all states hold recruiters to the same standard: to conduct timely and proper identification and recruitment of eligible migratory children.

The first step in the process of determining if children are eligible for the MEP, however, is to locate them. Chapter 4 provides specific information on how to find migratory children.

Chapter 4. Building a Recruitment Network

Chapter 4 Learning Objectives

Networking creates a supportive system to share information and services among individuals and groups having a common interest. (National ID&R Curriculum)

| Chapter 4 Learning Objectives |

|---|

|

The recruiter will learn how to |

|

identify the local organizations and individuals who work most closely with the migratory community; |

|

develop profiles of key local employees, school staff, community organizations, and the migratory community; |

|

determine the best way to build relationships with each of these key contacts (e.g., find out how they can be assisted, provide awareness training on the MEP); |

|

follow up regularly with key contacts, particularly when they provide leads on local migratory families (e.g., call or visit them, attend important meetings, send thank you notes); |

|

work with schools, community organizations, etc., to see if they will include pre-screening questions for the MEP as part of their enrollment or intake process; and |

|

create a recruitment map that shows areas where migratory families are likely to live and work, services they use, and where their children go to school. |

Finding Migratory Children